- Home

- Dennis Wheatley

The Sword of Fate Page 3

The Sword of Fate Read online

Page 3

She should mark out a triangle in the dust on the ground between any three palm trees; then, carrying a fair-sized bowl of fresh water and the enclosed amulet, she should enter the triangle. Placing the bowl of water on the ground, Miss Diamopholus should walk three times round it with the amulet clasped in her right hand. She should then halt, facing north, and, on the stroke of midnight, she should kneel down, pressing the amulet to her heart. She will then see, reflected on the surface of the water, the face of the man whom she is to marry.

Of course, the whole thing was the most utter hocus-pocus, but I do not think that any land in the world is so superstition-ridden as Egypt and I felt that it was a safe bet that Daphnis, being a member of a family which had lived in Egypt for hundreds of years, would be a convinced believer in the power of amulets to foretell the future.

The full moon was due two nights hence and, since she would neither come out with me nor receive me at her home, I hoped to lure her into the garden after her family had gone to bed. I had said any three palm trees, but I was counting on the fact that, since three palm trees stood just below the windows at the back of the house, she would hardly be able to resist trying out the experiment there.

Most of my second week of leave had been spent in hospital, and actually I was due to return to my unit on the night of the full moon; but I was not unduly perturbed by that as I felt confident that I could obtain convalescent leave as a result of my smash, and so it proved. On the sixth day after the accident I was discharged and granted six days’ additional furlough to recuperate before reporting back for duty.

That afternoon I visited the Arab seamen’s quarter down by the docks and I did not have to pick my way far through the filth and garbage that litters those evil-smelling narrow streets before I found what I wanted—a ship’s chandler. There I bought a grapnel which would have served to anchor a small boat, and a twenty-foot coil of thin rope, both of which I took back to the hotel with me, wrapped up in a piece of sacking.

I confess to a certain suppressed excitement as I sat down to dinner in the restaurant that evening; and, as I did not wish to have my thoughts distracted by casual conversation with people in the lounge afterwards, I decided to draw out the meal as long as possible. For that reason I ordered my favourite dishes, a special sweet and a bottle of champagne, then lingered over a double ration of coffee and a couple of Benedictines.

By the time I had done there was not very long to while away as I meant to walk to the back of ‘millionaires’ row’ and to be in the Diamopholi garden before there was any chance of Daphnis coming out into it; so that I could conceal myself there and there would be no risk of her being frightened away by the noise of my coming in over the wall.

When I left the hotel I was carrying the grapnel and rope in its wrapping of sacking and over my brown shoes I had on a pair of goloshes that I had bought that afternoon. The night was fine, but the full moon was not showing to its best advantage as the sky was cloudy. I looked on that as a sign that Venus favoured my intentions, as, in brilliant moonlight, I should have stood much more risk of being spotted and taken for a burglar when I attempted to scale the high wall.

I arrived in the street behind the Diamopholi mansion at twenty past eleven. Few people were about and the silence was only disturbed by the passing of an occasional car along the main road some distance away. I tried the little door in the wall, but, as I expected, it was locked. Stepping back into the road I made quite certain that no one was approaching, then took the grapnel and rope from the sacking. Grasping the extreme end of the rope firmly, I flung the grapnel high into the air so that it sailed right over the top of the eighteen-foot wall.

It hit the brickwork on the far side with a sharp clink, but no other sound followed, so I gently hauled in on the rope until the grapnel came up and, my luck being in, hooked itself firmly at the very first trial on to the wall. I then used the rope to support the weight of the upper part of my body and swung my feet out flat against the wall, so that, going up hand over hand, I could virtually walk up it, thus preventing the old brickwork dirtying my uniform, except when I had to straddle the wall on reaching its top. Having refixed the grapnel and transferred the rope to the far side, I lowered myself into the garden and, all things considered, arrived there with remarkably little dust or dirt on my hands and clothes.

Enough moonlight was percolating through breaks in the clouds to show me the lay-out of the garden. It was little more than a large oblong sandy courtyard, with the three palm trees in the middle and a few formal beds of flowers at each side. Fortunately there were a few shrubs against the bottom wall to hide behind if necessary, and at the far end near the house I could just discern what appeared to be a small sunk garden with a fountain in its centre.

It was barely half past eleven so I thought I would investigate the place a little further before settling down in the most convenient hide-out. The back of the house was in complete darkness, so it seemed as though the family had already gone to bed. I advanced cautiously along one of the side walls until I was level with the nearest palm tree. It was then, for the first time, I suddenly became aware that I was not alone in the garden.

With alarming unexpectedness a match flared as someone near the fountain lit a cigarette and in the flame I just caught a glimpse of a man’s face. He was looking my way and had his back to the house, from which he was hidden by some ornamental brickwork.

At the first spark I had gone dead still, knowing that if I remained so it was most unlikely that my outline would be distinguishable from the other shadows among which I stood; and, almost at once, I caught the sound of lowered voices. The man was not alone, and although I could not catch any distinct words, the tone in which the two people were talking told me that they were in earnest conversation.

Whoever they were, they presumably had a right there, whereas I had not, and if the moon suddenly came out they could hardly fail to catch sight of me before I should have time to get under cover. With cautious footsteps I beat a hasty retreat to the bottom of the garden, where I selected the thickest patch of bushes and sat down behind them patiently to await events.

For the best part of quarter of an hour nothing happened. I was too far off now either to see or hear anything of the two people near the fountain but at last the sound of footsteps told me that they had come out of their concealment and were approaching. The moon was now hidden completely so I could hardly see a thing, and as the footsteps grew nearer I sensed rather than saw that the man’s companion was a girl.

At the postern door they halted and they could not have been standing much more than two yards from me. A key turned in the lock, then the girl’s voice came quite clearly. It was Daphnis and she was speaking in Italian.

“I do hate all this subterfuge. Can’t you possibly make some arrangement with Mother so that we can meet openly?”

My heart seemed to go down into my boots. Evidently she already had a lover and one in whom she was sufficiently interested to allow him to meet her clandestinely by night, so it seemed that there was little hope for me. Before I could speculate further upon this depressing revelation, the man replied, also speaking in Italian:

“But, my dear, your stepfather would never allow it. He hates me like poison. No, our meetings must continue to be in secret and it is better so; otherwise someone might become suspicious, and that would ruin everything.”

I took the words in automatically, thinking little of their sense. It was their tone which riveted my entire attention. I knew that voice; I had heard it somewhere before. Where I could not think, but it had a ring about it that was quite unmistakable; a self-opinionated arrogance, tempered with a mock-politeness, and in my mind it was associated with a memory that was definitely disagreeable. Strive as I would, I could not recall the circumstances in which I had heard that voice before, but every fibre of my being cried out to me that I had reason to fear and hate its owner.

Chapter III

Under a Clouded Moon

As she disappeared in the shadows, I turned my face to the wall, lit a cigarette and, rising from my cramped position, stood up with the cigarette cupped carefully in my hand so that the burning end of it would not show.

I wondered if it was worth waiting now, and rather doubted it. Whether she was superstitious or not, Daphnis was hardly likely to be much intrigued by an amulet, sent her by a young man she hardly knew, when she was already deeply involved in a secret love affair. Still, there could not be much more than six or seven minutes to go till midnight, and it seemed silly not to make quite certain that I had entirely wasted my evening, before climbing back over the wall.

As I stood smoking there, I noticed that the clouds had become much more broken and that the moonlight was now filtering through sufficiently to fill the garden with a dim, uncertain light. Just as I had finished my cigarette, there came faintly on the light breeze the call to prayer of a muezzin from some distant minaret in the centre of the town. It was midnight but there was no sign of Daphnis.

I thought with regret of how I had planned to carry my ruse to its logical conclusion. During the whole of that day there had never been far from my thoughts the exciting vision of Daphnis walking round the bowl of water, then kneeling down facing the north, which was towards the house and would mean that her back was turned towards me, while I crept noiselessly up behind her and peered over her shoulder so that it should be my face which would be reflected on the moonlit surface. As bitterly disappointed as though the little scene had actually been promised to me, I was about to grasp the dangling rope when I caught sight of something whitish moving in the moonlight near the house.

Next moment I felt a terrific thrill. It was Daphnis. She had come out again, and as she approached I saw that she was wearing a loose white woollen robe over her dress, which had big full sleeves and was tightly girded at the waist.

When she reached the middle of the three palm trees she halted, but she carried no bowl of water with her and just stood there, apparently waiting for something to happen. I was in two minds whether to emerge from my hiding-place at once or to wait for a little to see what she would do when, quite unexpectedly, the question was answered for me. It was very still there in the garden, and although she spoke hardly above a whisper, I heard her say distinctly:

“Mr. Day, where are you?”

Feeling the most awful fool, I came out from behind the bushes and walked across to her. With a rather sheepish smile I murmured: “Good evening. How clever of you to guess that I meant to appear in person!”

“It didn’t need much intelligence to see through that business of the amulet,” she said slowly; “particularly as it seems that you’re determined to get me into trouble.”

“Oh, come!” I protested. “You know that I don’t want to do that, but I simply had to see you again somehow.”

The moon had now come out from behind the clouds. It was shining on her face, and as she stood in front of me I thought her more lovely than ever.

“You’re the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen,” I hurried on. “I’m simply crazy about you!” And to lend force to my words I seized one of her hands and pressed it in both of mine.

In the past I had often said much the same sort of thing to other girls. Women always seem to expect it if you make love to them, but this time I was not acting and I think the earnestness of my voice must have carried conviction. She did not seek to draw away her hand and she smiled.

“You only saw me for a few minutes after you had had that awful crack on the head so you can’t possibly be in love with me.”

“But I am—desperately.”

“That’s a pity, because we live in different worlds. Nothing could come of it.”

“Nonsense!” I said almost rudely. “How old are you, Daphnis?”

“Eighteen.”

“You’re quite old enough to know your own mind and follow your own inclinations,” I said. “Tradition is all very well, and I know it’s the custom among the wealthy Greek families of Alex to keep themselves very much to themselves, but we’re living in an age when women smoke, wear trousers and drink cocktails—in fact, they do as they darn’ well please, so why shouldn’t you—er—er—form a friendship with a British officer?”

“I’ve told you already that nothing could come of it, and I—well, I’m not certain that I want to.”

“You knew I meant to get into this garden tonight, and you came down to meet me. If you didn’t want to be friends, why did you do that?” I asked with a smile.

Her answer came without hesitation and its frankness was positively startling, “I couldn’t resist the temptation to see if you really were as good-looking as I thought you the other day.”

I laughed a little awkwardly: “If I were as good-looking a man as you’re beautiful a girl, I’d be the handsomest fellow in the world.”

It was a clumsy compliment, but for some extraordinary reason I was finding it infinitely more difficult to say the right things to this girl with whom I had fallen so genuinely in love than I ever had to women like Oonas or Deirdre, with whom I was only amusing myself. Yet, somewhat to my surprise, she took my words quite seriously, and opening her wide big eyes she said:

“Do you really believe that I am as beautiful as all that?”

I raised her little warm hand and kissed it as I murmured, “You’re more lovely than the Princess out of any story from The Arabian Nights.”

“I think we’re both a little mad,” she said suddenly. “I certainly should be if I believed you. As it is I’m taking a crazy risk, standing here talking to you in the full moonlight. At any moment, if any of the servants happened to wake up and look out of the window they would see me.”

“Let’s go into the shadow, then.” I quickly took her arm and drew her along one of the side-walks to where a few steps led down to the fountain. There was a stone seat in a corner there which was out of view of the house. As we sat down on it she gently removed her arm from my clasp. Producing my cigarette-case, I offered it and she took one. After I had lit it for her she said with a sigh:

“I’d never dare to do this if Mother were at home.”

“What, smoke?” I asked, perhaps a little stupidly.

She laughed. “Of course not! I often smoke and I wear trousers, and no one would stop me drinking cocktails if I wanted to. I meant sit out here with you.”

“Your mother’s away, then?”

“Yes. She’s staying with friends in Cairo and is not due back until the day after tomorrow.”

Silence fell between us and we just sat there, smoking nervously. Why, I can’t think, but all my savoir faire seemed suddenly to have deserted me. I never remember having been tongue-tied before, but I simply could not think of a single opening to resume our conversation. Everything that occurred to me seemed banal, stupid or facetious. Perhaps Daphnis had this extraordinary effect on me because she was so different from any other girl that I had ever met, but, fortunately, she did not seem to notice the frustration and mortification that I was feeling. It was she who at last broke our long silence.

“How long have you been stationed in Alexandria?”

“I’m only here on leave,” I told her, “and I should have returned to my unit tonight, but owing to the crash I’ve now got an extra six days.”

“Is your head quite all right now?”

“Yes, thanks. It was pretty painful at first, but for the last few days I’ve suffered no ill-effects except slight headaches.”

Again that silence, so strange and so embarrassing to me, fell between us. There were a hundred things that I wanted to ask her and I knew so well that I was absolutely throwing away those golden moments when I should have been

exerting myself to the utmost to entertain and interest. Yet somehow that half-serious, half-amusing chatter which usually came so glibly to my tongue when I was alone like this with a girl continued to elude me.

We could not have been sitting there much more than ten minutes, although it seemed like an hour, when she suddenly stood up and announced:

“It’s getting late. I must go in.”

“No, no, please don’t!” I protested hastily. “I’ve got so much that I want to say to you.”

“Really!” Her eyebrows arched and the smile which, when it appeared, seemed to light up her whole face, came again. “I was beginning to think that you were one of those strong, silent men that women novelists write about.”

“I’m not,” I assured her, “not in the ordinary way, at least. It’s just the absolutely devastating effect that you have on me.”

“Whatever do you mean?”

“Simply that, normally, I’ve always got masses of things to talk about, and that, for the whole of the past week, I’ve been simply dying to talk to you; but, now that I’ve got the chance, I feel as shy and tongue-tied as a boy of sixteen at his first dance.”

“You know,” she said, “I believe you really mean that and it’s the nicest thing you could possibly have said; but I’m going in now, all the same.”

For a moment I was torn between two urges: the one to make her stay because I could not bear that she should rob me of her presence so soon; the other, springing from the few wits which were all that I seemed able to retain while with her, that having quite fortuitously, by my long awkward silences, created a better impression with her than I ever could have done by amusing banter and glib flattery, wisdom dictated that I should not jeopardise my gain by pressing her to remain.

She held out her hand and I kissed it, but before I released it I said swiftly, “If you insist on going now, at least promise to let me see you again.”

Traitors' Gate gs-7

Traitors' Gate gs-7 Gunmen, Gallants and Ghosts

Gunmen, Gallants and Ghosts They Used Dark Forces gs-8

They Used Dark Forces gs-8 Gateway to Hell

Gateway to Hell The Rape Of Venice rb-6

The Rape Of Venice rb-6 Traitors' Gate

Traitors' Gate They Used Dark Forces

They Used Dark Forces The Shadow of Tyburn Tree rb-2

The Shadow of Tyburn Tree rb-2 The Dark Secret of Josephine

The Dark Secret of Josephine The Secret War

The Secret War The Forbidden Territory

The Forbidden Territory To The Devil A Daughter mf-1

To The Devil A Daughter mf-1 The Sultan's Daughter rb-7

The Sultan's Daughter rb-7 The Launching of Roger Brook rb-1

The Launching of Roger Brook rb-1 The Quest of Julian Day

The Quest of Julian Day The Irish Witch

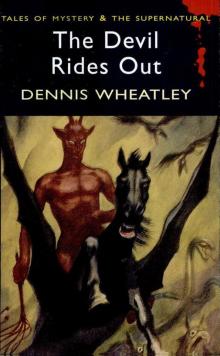

The Irish Witch The Devil Rides Out ddr-6

The Devil Rides Out ddr-6 The Golden Spaniard

The Golden Spaniard Black August

Black August Mayhem in Greece

Mayhem in Greece The Eunuch of Stamboul

The Eunuch of Stamboul Strange Conflict

Strange Conflict The Rising Storm rb-3

The Rising Storm rb-3 The Rising Storm

The Rising Storm Such Power is Dangerous

Such Power is Dangerous Uncharted Seas

Uncharted Seas The wanton princess rb-8

The wanton princess rb-8 Codeword Golden Fleece

Codeword Golden Fleece The Black Baroness

The Black Baroness The White Witch of the South Seas

The White Witch of the South Seas The Ravishing of Lady Jane Ware rb-10

The Ravishing of Lady Jane Ware rb-10 They Found Atlantis

They Found Atlantis Come into my Parlour

Come into my Parlour The Second Seal

The Second Seal Unholy Crusade

Unholy Crusade The Satanist

The Satanist The Satanist mf-2

The Satanist mf-2 The White Witch of the South Seas gs-11

The White Witch of the South Seas gs-11 The Sultan's Daughter

The Sultan's Daughter Vendetta in Spain ddr-2

Vendetta in Spain ddr-2 Dangerous Inheritance

Dangerous Inheritance The Sword of Fate

The Sword of Fate The Scarlet Impostor

The Scarlet Impostor The Ka of Gifford Hillary

The Ka of Gifford Hillary The Black Baroness gs-4

The Black Baroness gs-4 The Devil Rides Out

The Devil Rides Out The Prisoner in the Mask

The Prisoner in the Mask To the Devil, a Daughter

To the Devil, a Daughter The Haunting of Toby Jugg

The Haunting of Toby Jugg Sixty Days to Live

Sixty Days to Live Faked Passports

Faked Passports Mediterranean Nights

Mediterranean Nights The Strange Story of Linda Lee

The Strange Story of Linda Lee The Island Where Time Stands Still

The Island Where Time Stands Still The Wanton Princess

The Wanton Princess The Ravishing of Lady Mary Ware

The Ravishing of Lady Mary Ware V for Vengeance

V for Vengeance Star of Ill-Omen

Star of Ill-Omen Contraband gs-1

Contraband gs-1 The Fabulous Valley

The Fabulous Valley The Dark Secret of Josephine rb-5

The Dark Secret of Josephine rb-5 Bill for the Use of a Body

Bill for the Use of a Body Curtain of Fear

Curtain of Fear Faked Passports gs-3

Faked Passports gs-3 The Rape of Venice

The Rape of Venice The Man who Killed the King

The Man who Killed the King The Shadow of Tyburn Tree

The Shadow of Tyburn Tree Black August gs-10

Black August gs-10 They Found Atlantis lw-1

They Found Atlantis lw-1 Evil in a Mask

Evil in a Mask Vendetta in Spain

Vendetta in Spain The Launching of Roger Brook

The Launching of Roger Brook The Man who Missed the War

The Man who Missed the War Evil in a Mask rb-9

Evil in a Mask rb-9 Three Inquisitive People

Three Inquisitive People The Irish Witch rb-11

The Irish Witch rb-11 Contraband

Contraband