- Home

- Dennis Wheatley

To The Devil A Daughter mf-1

To The Devil A Daughter mf-1 Read online

To The Devil A Daughter

( Molly Fountain - 1 )

Dennis Wheatley

Miles away, in the mist and rain of the Essex marshes, a satanic priest has created a hideous creature. Now it was waiting beneath the ancient stones of Bentford Priory for the virgin sacrifice that would give it life . . .

Revew

Why did the solitary girl leave her rented house on the French Riviera only for short walks at night? Why was she so frightened? Why did animals shrink away from her? The girl herself didn't know, and was certainly not aware of the terrible appointment which had been made for her long ago and was now drawing close.

Molly Fountain, the tough-minded Englishwoman living next door, was determined to find the answer. She sent for a wartime secret service colleague to come and help. What they discovered was horrifying beyond anything they could have imagined.

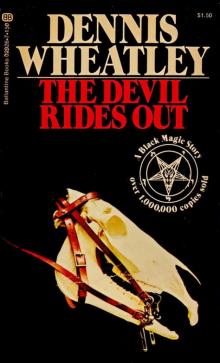

Dennis Wheatley returned in this book to his black magic theme which he had made so much his own with his famous best seller The Devil Rides Out. In the cumulative shock of its revelations, the use of arcane knowledge, the mounting suspense and acceleration to a fearful climax, he out-does even that earlier achievement. This is, by any standards, a terrific story.

To The Devil A Daughter

by Dennis Wheatley

By Dennis Wheatley

Novels

The Launching of Roger Brook

The Shadow of Tyburn Tree

The Rising Storm

The Man Who Killed the King

The Dark Secret of Josephine

The Rape of Venice

The Sultans Daughter

The Wanton Princess

Evil in a Mask

The Ravishing of Lady Mary Ware

The Irish Witch

Desperate Measures

The Scarlet Impostor

Faked Passports

The Black Baroness

V for Vengeance

Come into My Parlour

Traitors Gate

They Used Dark Forces

The Prisoner in the Mask

The Second Seal

Vendetta in Spain

Three Inquisitive People

The Forbidden Territory

The Devil Rides Out

The Golden Spaniard

Strange Conflict

Codeword Golden Fleece

Dangerous Inheritance

Gateway to Hell

The Quest of Julian Day

The Sword of Fate

Bill for the Use of a Body

Black August

Contraband

The Island Where Time Stands Still

The White Witch of the South Seas

To the Devil A Daughter

The Satanist

The Eunuch of Stamboul

The Secret War

The Fabulous Valley

Sixty Days to Live

Such Power is Dangerous

Uncharted Seas

The Man Who Missed the War

The Haunting of Toby Jugg

Star of Ill Omen

They Found Atlantis

The Ka of Gifford Hillary

Curtain of Fear

Mayhem in Greece

Unholy Crusade

1

Strange Conduct of a Girl Unknown

Molly Fountain was now convinced that a more intriguing mystery than the one she was writing surrounded the solitary occupant of the house next door. For the third morning she could not settle to her work. The sentences refused to come, because every few minutes her eyes wandered from the paper, and her mind abandoned its search for the appropriate word, as her glance strayed through the open window down to the little terrace at the bottom of the garden that adjoined her own.

Both gardens sloped steeply towards the road. Beyond it, and a two hundred feet fall of jagged cliff, the Mediterranean stretched blue, calm and sparkling in the sunshine, to meet on the horizon a cloudless sky that was only a slightly paler shade of blue. The road was known as the `Golden Corniche' owing to the outcrop of red porphyry rocks that gave the coast on this part of the Riviera such brilliant colour. To the right it ran down to St. Raphael; to the left a drive of twenty odd miles would bring one to Cannes. Behind it lay the mountains of the Esterel, sheltering it snugly from the cold winds, while behind them again to the north and east rose the great chain of snow tipped Alps, protecting the whole coast and making it a winter paradise.

Although it was only the last week in February, the sun was as hot as on a good day in June in England. That was nothing out of the ordinary for the time of year, but Mrs. Fountain had long since schooled herself to resist the temptation to spend her mornings basking in it. Her writing of good, if not actually best seller, thrillers meant the difference between living in very reasonable comfort and a near precarious existence on the pension of the widow of a Lieutenant Colonel. As a professional of some years' standing she knew that work must be done at set hours and in suitable surroundings. Kind friends at home had often suggested that in the summer she should come to stay and could write on the beach or in their gardens; but that would have meant frequent interruptions, distractions by buzzing insects, and gusts of wind blowing away her papers. It was for that reason she always wrote indoors, although in the upstairs front room of her little villa, so that she could enjoy the lovely view. All the same, to day she was conscious of a twinge of envy as she looked down on the girl who was lazing away the morning on the terrace in the next garden.

With an effort she pulled her mind back to her work. Johnny, her only son, was arriving to stay at the end of the week, and during his visits she put everything aside to be with him. She really must get up to the end of chapter eight before she abandoned her book for a fortnight. It was the trickiest part of the story, and if she had not got over that it would nag at her all through his stay. And she saw so little of him.

Despite herself her thoughts now drifted towards her son. He was not a bit like his father, except in his open, sunny nature that so readily charmed everyone he met. Archie had been typical of the Army officer coming from good landed gentry stock. After herself, hunting, shooting and fishing had been his passions, and on any polo ground he had been a joy to watch. Johnny cared for none of those things. He took after her family, in nearly all of whom a streak of art had manifested itself. In Johnny's case it had come out as a flair for line and colour, and at twenty three his gifts had already opened fine prospects for him with a good firm of interior decorators. But that meant his living in London. He could only come out to her once a year, and she could not afford to take long holidays in England.

She had often contemplated selling the villa and making a home for him in London; but somehow she could not bring herself to do that. When she and Archie married in 1927 they had spent their honeymoon at St. Raphael, and fallen nearly as much in love with that gold and blue coast of the Esterel as they were with each other. That was why, when his father had died in the following year, they had decided to buy a villa there. As a second son his inheritance amounted to only a few thousands, but they had sunk nearly all of it in this little property and never regretted it. During the greater part of each year they had had to let it, but that brought them in quite a useful income, and for all their long leaves, while Johnny was a baby and later a growing boy, they had been able to occupy it themselves; so every corner of the house and every flowering shrub in the garden was intimately bound up with happy memories of her young married life.

The coming of the war had substituted long months of anxious separation for that joyful existence, and in 1942 all hope of its resumption had been finally shattered by an 8 mm. shell fired from one of Rommel's tanks in the Western Desert. Johnny had then b

een at school in Scotland, and his mother, her heart numb with misery, had striven to drown her grief by giving her every waking thought to the job she had been doing since 1940 in one of the Intelligence Departments of the War Office.

The end of the war had left her in a mental vacuum. Three years had elapsed since Archie's death, so she had come to accept it and was no longer subject to bouts of harrowing despair. But her job was finished and Johnny had just gone up to Cambridge; so she was now adrift without any absorbing interest to occupy the endless empty days that stretched ahead. Nearly six years of indifferent meals, taken at odd hours while working, often till midnight, on

Top Secret projects that demanded secretarial duties of the most conscientious type, had left her both physically and mentally exhausted; so when it was learned that the villa had not been damaged or looted of its furniture, her friends had insisted that she should go south to recuperate.

She went reluctantly, dreading that seeing it again would renew the intolerable ache she had felt during the first months after her loss. To her surprise the contrary had proved the case. If Archie's ghost still lingered there, it smiled a welcome in the gently moving sunlight that dappled the garden paths, and in the murmur of the sea creaming on the rocks there seemed to be a faint echo of laughter. It was the only permanent home they had ever had, and in these peaceful surroundings they had shared she found a new contentment.

For a few months her time had been amply filled in putting the house to rights, getting the neglected garden back into order and renewing her acquaintance with neighbours who had survived the war; but with her restoration to health her mind began to crave some intellectual occupation. Before the war she had occasionally written short stories for amusement and had had a few of them accepted; so it was natural that she should turn to fiction as an outlet. Besides, she had already realised that Archie's pension would be insufficient to support her at the villa permanently, and by then she had again become so enamoured of the place that she could not bear the thought of having to part with it. So, under the double spur, she set to work in earnest.

Very soon she found that her war time experiences had immensely improved her abilities as a writer. Thousands of hours spent typing staff papers had imbued her with a sense of how best to present a series of factors logically, clearly and with the utmost brevity. Moreover, in her job she had learned how the secret services really operated; so, without giving away any official secrets, she could give her stories an atmosphere of plausibility which no amount of imagination could quite achieve. These assets, grafted on to a good general education and a lively romantic mind,

had enabled her agent to place her first novel without difficulty. She had since followed it up with two a year and had now made quite a name for herself as a competent and reliable author.

Molly Fountain's books were set in a great variety of countries, but they were always mystery thrillers with a background of secret service. No one knew better than she that truth really was stranger than fiction; yet she never deliberately based a plot upon actual happenings to which she had been privy during the war. On the other hand, while taking considerable care to avoid any risk of an action for libel, she had no scruples about using as characters in her stories the exotic types frequently to be met with on that cosmopolitan coast, or incorporating such lurid doings as the tittle tattle of her bridge club in Cannes brought her, if these episodes could be profitably fitted in to add zest to the tale. That, subconsciously at least, was one of the reasons for her interest in the girl next door. Everything about this new neighbour suggested that she was the centre of a mystery.

Four days earlier Molly had just sat down to tea on her own little terrace when a taxi drew up in the road below and the girl had stepped out of it. She came from the direction of Cannes. In the taxi with her was a middle aged man and some hand luggage. From the time and circumstances of her arrival it could be inferred that she had not come south on the Blue Train, but had landed from a 'plane at Nice airport. The man who accompanied her was strongly built, stocky and aggressive looking, yet with something vaguely furtive about him. His clothes had struck a slightly incongruous note as he stood for a moment in the sunshine, looking up at the villa. It was not that there was anything really odd about them, and they were of quite good quality; but they were much more suited to a city office than either holidaying on the Riviera or travelling to it. He had helped the driver carry the suitcases up to the house, but remained there only about ten minutes, then returned to the waiting taxi and was driven off in it. That was the first and only time that Molly had seen him, and it now seemed evident that, having gone, he had gone for good.

There was nothing peculiarly strange in that. He might have been a house agent who had arranged to meet the girl and take her out to the villa that she had rented on a postal description through his firm; but in spite of his office clothes he had looked much too forceful a personality to be employed on such comparatively unimportant tasks. It seemed more probable that he was a relative or friend giving valuable time to performing a similar service. Anyhow, whoever he was, he had not bothered to come near the place again.

The strange thing was that no one else had either; nor, as far as Molly knew, had the girl ever gone out at least in the daytime and there was certainly something out of the ordinary about a young woman who was content to remain without any form of companionship for three whole days.

Stranger still, she made not the least effort to amuse herself. She never brought out any needlework or a sketching block, and was never seen to write a letter. Even when she carried a book as far as the terrace she rarely read it for more than a few minutes. Every morning, and a good part of each afternoon, she simply sat there gazing blankly out to sea. The theory that she was the victim of a profound sorrow suggested itself, yet she wore no sign of mourning and her healthy young face showed no trace of grief.

Molly had never encouraged her servants to bring her the local gossip, but in this case so intrigued had she become that she had made an exception. Like most women with a profession, she was too occupied to be either fussy or demanding about her household, provided she was reasonably well served; so she still had with her a couple named Botin whom she had engaged on her return to France in 1946. They had their faults, but would allow no one to cheat her except themselves, and that only in moderation. They were middle aged, of cheerful disposition and had become much attached to her. Louis looked after the garden and did the heavy work, while Angele did the marketing, the cooking and all those other innumerable tasks which a French bonne a tout faire so willingly undertakes. On the previous day Molly had, with apparent casualness, pumped them both.

Louis produced only two crumbs of information, gleaned from his colleague, old Andre, who for many years had tended the adjoining garden. The mademoiselle was English and the villa had been taken for only a month. Angele had proved an even poorer source, as she reported that the borne who was looking after the young lady next door was a stranger to the district; she had been engaged through an agency in Marseilles and was a Catalan, a woman of sour disposition who had rejected all overtures of friendship and was uncommunicative to the point of rudeness.

Negative as Angele's contribution appeared to be, it had given Molly further food for speculation. Why should an English visitor engage a semi foreigner from a city a hundred miles away to do for her, when there were plenty of good bonnes to be had on the spot? It would have saved a railway fare, and quite a sum on the weekly household books, to secure one who was well in with the local shopkeepers and knew the best stalls in the St. Raphael market at which to buy good food economically. The ,answer that sprang to mind was that a stranger was much less likely to gossip, and therefore something was going on next door that the tenant desired to hide.

Then, last night the mystery had deepened still further. Molly was a light sleeper. A little after one o'clock she had been roused by the sound of a loose stone rattling down the steep slope of a garden path. Getting out of b

ed she went to the window. The moon was up, its silvery light gleaming in big patches on the cactus between the pine trees, and there was the girl just going down the short flight of steps that led from her little terrace to the road.

Fully awake now, Molly turned on her bedside light and settled down to read a new William Mole thriller that she had just had sent out from England; but while reading, her curiosity about her neighbour now still further titillated, she kept an ear cocked for sounds of the girl's return. As a writer she could not help being envious of the way in which Mr. Mole used his fine command of English to create striking imagery, and her sense of humour was greatly tickled by his skilful interpolation of the comic between his more exciting scenes; so the next hour and a half sped by very quickly. Then in the still night she heard the click of the next door garden gate, and, getting up again, saw the girl re enter the house.

Why, Molly wondered, when she never went out in the daytime, should she go out at night? It could hardly be that she was in hiding, because she spent the greater part of each day on the terrace, where she could easily be seen from the road by anyone passing in a car. The obvious answer seemed to be that she had gone out to meet someone in secret; but she had been neither fetched in a car nor returned in one, and she had not been absent quite long enough to have walked to St. Raphael and back. Of course, she could have been picked up by a car that had been waiting for her round the next bend of the road, or perhaps she had had an assignation at one of the neighboring villas. In any case, this midnight sortie added still further to the fascinating conundrum of what lay behind this solitary young woman having taken a villa on the Corniche d'Or.

For the twentieth time that morning Molly's grey green eyes wandered from her typewriter to the open window. Just beneath it a mimosa tree was in full bloom and its heavenly scent came in great wafts to her. Beyond it and a little to the left a group of cypresses rose like dark candle flames, their points just touching the blue horizon. Further away to the right two umbrella pines stood out in stark beauty against the azure sky. Below them on her small, square, balustraded terrace the girl still sat motionless, her hands folded in her lap, gazing out to sea. About the pose of the slim dark haired figure there was something infinitely lonely and pathetic.

Traitors' Gate gs-7

Traitors' Gate gs-7 Gunmen, Gallants and Ghosts

Gunmen, Gallants and Ghosts They Used Dark Forces gs-8

They Used Dark Forces gs-8 Gateway to Hell

Gateway to Hell The Rape Of Venice rb-6

The Rape Of Venice rb-6 Traitors' Gate

Traitors' Gate They Used Dark Forces

They Used Dark Forces The Shadow of Tyburn Tree rb-2

The Shadow of Tyburn Tree rb-2 The Dark Secret of Josephine

The Dark Secret of Josephine The Secret War

The Secret War The Forbidden Territory

The Forbidden Territory To The Devil A Daughter mf-1

To The Devil A Daughter mf-1 The Sultan's Daughter rb-7

The Sultan's Daughter rb-7 The Launching of Roger Brook rb-1

The Launching of Roger Brook rb-1 The Quest of Julian Day

The Quest of Julian Day The Irish Witch

The Irish Witch The Devil Rides Out ddr-6

The Devil Rides Out ddr-6 The Golden Spaniard

The Golden Spaniard Black August

Black August Mayhem in Greece

Mayhem in Greece The Eunuch of Stamboul

The Eunuch of Stamboul Strange Conflict

Strange Conflict The Rising Storm rb-3

The Rising Storm rb-3 The Rising Storm

The Rising Storm Such Power is Dangerous

Such Power is Dangerous Uncharted Seas

Uncharted Seas The wanton princess rb-8

The wanton princess rb-8 Codeword Golden Fleece

Codeword Golden Fleece The Black Baroness

The Black Baroness The White Witch of the South Seas

The White Witch of the South Seas The Ravishing of Lady Jane Ware rb-10

The Ravishing of Lady Jane Ware rb-10 They Found Atlantis

They Found Atlantis Come into my Parlour

Come into my Parlour The Second Seal

The Second Seal Unholy Crusade

Unholy Crusade The Satanist

The Satanist The Satanist mf-2

The Satanist mf-2 The White Witch of the South Seas gs-11

The White Witch of the South Seas gs-11 The Sultan's Daughter

The Sultan's Daughter Vendetta in Spain ddr-2

Vendetta in Spain ddr-2 Dangerous Inheritance

Dangerous Inheritance The Sword of Fate

The Sword of Fate The Scarlet Impostor

The Scarlet Impostor The Ka of Gifford Hillary

The Ka of Gifford Hillary The Black Baroness gs-4

The Black Baroness gs-4 The Devil Rides Out

The Devil Rides Out The Prisoner in the Mask

The Prisoner in the Mask To the Devil, a Daughter

To the Devil, a Daughter The Haunting of Toby Jugg

The Haunting of Toby Jugg Sixty Days to Live

Sixty Days to Live Faked Passports

Faked Passports Mediterranean Nights

Mediterranean Nights The Strange Story of Linda Lee

The Strange Story of Linda Lee The Island Where Time Stands Still

The Island Where Time Stands Still The Wanton Princess

The Wanton Princess The Ravishing of Lady Mary Ware

The Ravishing of Lady Mary Ware V for Vengeance

V for Vengeance Star of Ill-Omen

Star of Ill-Omen Contraband gs-1

Contraband gs-1 The Fabulous Valley

The Fabulous Valley The Dark Secret of Josephine rb-5

The Dark Secret of Josephine rb-5 Bill for the Use of a Body

Bill for the Use of a Body Curtain of Fear

Curtain of Fear Faked Passports gs-3

Faked Passports gs-3 The Rape of Venice

The Rape of Venice The Man who Killed the King

The Man who Killed the King The Shadow of Tyburn Tree

The Shadow of Tyburn Tree Black August gs-10

Black August gs-10 They Found Atlantis lw-1

They Found Atlantis lw-1 Evil in a Mask

Evil in a Mask Vendetta in Spain

Vendetta in Spain The Launching of Roger Brook

The Launching of Roger Brook The Man who Missed the War

The Man who Missed the War Evil in a Mask rb-9

Evil in a Mask rb-9 Three Inquisitive People

Three Inquisitive People The Irish Witch rb-11

The Irish Witch rb-11 Contraband

Contraband